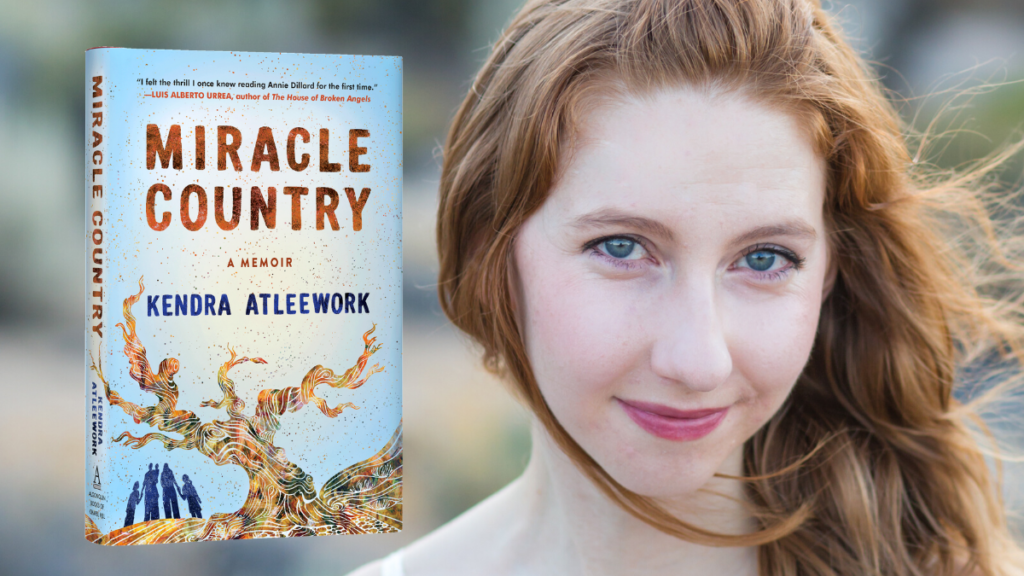

Read This Excerpt from Miracle Country

Kendra Atleework‘s debut book Miracle Country is a memoir of a person, a family—and a place. She grew up in Swall Meadows, California, in the Owens Valley of the Eastern Sierra Nevada, where annual rainfall averages five inches and in drought years measures closer to zero. And in this excerpt from Miracle Country, she explains how that shapes the people who live there.

To understand the place we call the Eastern Sierra, you must be able to see what is no longer here. See what hides, change your definition of big and empty and small, of good and bad. Bend and search the desert floor for the near-invisible petals of a crowned muilla and then look up to mountains that seem to rise forever. This dusty margin of California draws and then replicates the kind of people who have never completely adjusted to a human scale. They don’t quite fit other places, be it the orbit of their ideas, good and bad, or the size of the sky they require in order to carry out their lives. The author Mary Austin wandered west from Illinois in 1888, fell into the California desert, and remained for a long time. She wrote of the place, “You will find it forsaken of most things but beauty and madness and death and God.”

Mary Austin came to the Eastern Sierra in 1892. She lived in a brown house in Independence, one of the little towns strung along the highway in Owens Valley, where she wrote novels and essays and stories and plays about the strange presence of the land. As she told it, there was something about this country — “something that rustled and ran, that hung half-remotely, insistent on being noticed, fled from pursuit, and when you turned from it, leaped suddenly and fastened on your vitals.”

I walked around Swall Meadows, and it was not the same. I looked from my bedroom over the old view, the ridge of Wheeler blackened and in places still smoldering. I could not arrange myself anywhere in Swall so that my field of vision did not include evidence of fire.

But once the smoke cleared from the valley, the days after the burn were perfect blue and warm. We were first evacuated from Swall when I was too young to remember much besides snow lying over the mountain and burying our driveway, my father pushing the snowblower, a plume drifting over his shoulder like the tail of a white bird. That February, twenty years ago, we drove to Bishop in case of avalanche, which had swept houses off foundations in decades past. An avalanche had flipped a landmark on Wheeler Crest, a hundred-ton granite boulder Pop nicknamed House Rock, so that it pointed toward the sky.

I had evacuated for wildfire before, too, but that was in July. “Beautiful country burn again,” wrote the poet Robinson Jeffers in 1926, words that have become famous in California.

If the mountains are burning in February, my neighbors ask, what will summer bring? The streams that encircle Swall Meadows haven’t rushed the way I remember in a while. How starkly different each season once felt. In high school, I remember wet feet because I refused to wear boots. The roof over our lockers collapsed every year under snow. Lately, when I visit home in December, it seems I have traveled to a land of constant warmth, the myth of Southern California stretching north. Back in Minnesota, I tell people, “When I was home this summer,” then recall it was winter.

Swall marks the border between desert and sky. Mostly the mountain is dry, the valley brown, but meadows spread to the west where my brother and sister and I used to roam. There, rosehips grow thick enough to tear denim, and a grove of water birch and willow hugs a snowmelt creek. Years ago my father discovered a clearing beneath a roof of leaves, water running over crumbled granite. Grasses on the banks were flattened by the sleeping weight of mule deer or mountain lions. We called the place the Fairy Glen, and on summer afternoons we walked there with Mom to make mud balls and grass crowns and to pan for fool’s gold in the cold water. Pop bent green water birch branches into our hands, let go, and we launched twelve feet into the air. With my friend Daniel, I pulled the tailgate off an old truck burned in a fire in the 1980s and abandoned to the brush. We dragged the tailgate to the Fairy Glen and laid it as a footbridge across the stream.

After the fire, Daniel wrote to see if my house was okay. He grew up thirty minutes northwest in another Eastern Sierra town deeper in the mountains, called Mammoth Lakes. Now he lives in a wet, green place and works with trees. Sometimes he wants to move home. Then he thinks better of it.

“California is gonna get really scary, I think,” he said. “Crazy how things change in a decade . . . fires in February.” Beautiful country burn again. I told Daniel what the Fairy Glen looks like now: mostly gone. My hand ghostly against the blackened trunk of a water birch.

Walking the neighborhood, I saw women and men standing on driveways in front of warped water heaters, half-melted sewing machines, skeleton motorcycles, a spiral staircase leading nowhere.

“It’s not if it’s gonna happen again,” a volunteer firefighter told me. His house, once resting beside poplar trees across from ours, had vaporized. He watched it burn as he fought the fire, saw flames spilling into the street as his fire truck rumbled toward his driveway—thought no—then turned his back and went on to other houses. “It’s not if, it’s when,” he said. “It might be thirty years. We could lose twice as many next time.” A pause. Smoke drifting from a hot spot on the mountain.