Read this Excerpt from The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream

In the span of fifteen years, Dr. Thomas Neill Cream murdered as many as ten people in the United States, Britain, and Canada, a death toll with almost no precedent. Poison was his weapon of choice. In The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream, author Dean Jobb transports readers to the late nineteenth century as Scotland Yard traces Dr. Cream’s life through Canada and Chicago and finally to London, where new investigative tools called forensics were just coming into use. Read this excerpt from The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream now:

Prologue

Ghosts

{ Joliet, Illinois • July 1891}

The iron door of the Illinois State Penitentiary in Joliet groaned open and spat a haggard-looking man into the world he had left almost a decade earlier. It was the final day of July 1891, a clear-sky Friday. High above the man’s head, atop the gray limestone walls of the penitentiary forty miles southwest of Chicago, men in blue coats toting Winchester rifles watched him walk away. If this had been an escape, a single guard could have pumped sixteen bullets into his back without reloading.

Thomas Neill Cream’s hollow cheeks and sharp-edged features were the legacy of years at hard labor and stints in the mind-crushing hell of solitary confinement. He had traded his zebra-striped prison uniform for a new suit—a modest gift, like the ten dollars in his pocket, from the State of Illinois. His few belongings were stuffed into a pillowcase. He was also entitled to a train ticket to his place of conviction, but it’s unlikely he had a desire to return to Belvidere, a city in northern Illinois. Staff at the prison—known as Joliet— stopped cropping an inmate’s hair in the weeks before release and the men could grow a mustache or beard, helping them blend in. But the practice had made little difference to Cream, who was almost completely bald. Besides, after marching day after day in lockstep with fellow inmates—pressed together, single file, inching along like a giant striped caterpillar—many walked with the shuffling gait that betrayed them as former inmates. “The stripes,” noted Joliet’s warden, Robert McClaughry, “show through his citizen’s clothes.”

Cream had been inside for nine years and 273 days. Chester Arthur had just become president, replacing the assassinated James Garfield, when he began serving his sentence in November 1881. Grover Cleveland had won and lost the presidency in the meantime and now Benjamin Harrison occupied the White House. People who peered into the eyepiece of a prototype of Edison’s kinetoscope, unveiled a few weeks earlier, were astounded to see moving images. The telephone, a novelty in the early 1880s, was now installed in almost a quarter-million American homes and offices. In Springfield, Massachusetts, brothers Charles and J. Frank Duryea were tinkering with a prototype they called the “Motor Wagon”—America’s first gasoline-powered automobile.

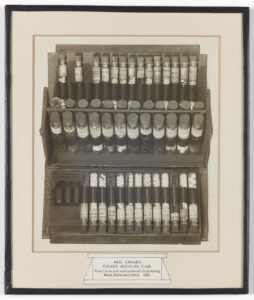

Even crime fighting had changed during Cream’s confinement. A few years before his release, an array of odd-looking calipers and measuring sticks had arrived at Joliet. Calibrated in centimeters and millimeters—metric-system increments rarely used in the United States— the devices were designed to precisely record the size of specific parts of the body. This pioneering system of identifying criminals bore a name as strange and foreign as the tools it required: bertillonage.

The system was based on eleven measurements, including a person’s overall height, the width of the head, the dimensions of the ear, the size of the left foot and the forearm, and the length of the middle and ring fingers. Subjects were also measured in a sitting position and with their arms outstretched. While two men might be found to have the same-sized foot, the chances of multiple measurements being identical were remote, and the odds of finding two subjects with identical sets of all eleven measurements was estimated at one in more than four million. To make a misidentification even more unlikely, the subject’s face was photographed, and eye color and any tattoos or scars were recorded. The system “renders the identification of felons and chronic law breakers . . . an absolute certainty,” claimed Joliet’s records clerk, Sidney Wetmore. “Mistake is impossible.”

Bertillonage was touted as a scientific solution to a challenge that had long faced the police and the courts: how to identify recidivists, ensuring they did not receive the more lenient treatment afforded first-time offenders. Some police forces and prison officials had already begun to photograph those arrested or incarcerated. Police in Birmingham, England, had led the way in the 1850s, marching suspects to a photographic studio to pose for some of the earliest mug shots. The practice was well established at Joliet by the time Cream arrived in 1881, and his photograph was added to the prison’s ever expanding rogues’ gallery. Illinois law demanded that repeat offenders be identified and punished accordingly—a conviction for a second serious offense carried a minimum fifteen-year prison term, while third offenders faced at least twenty years. But photographs were not a foolproof method for keeping tabs on criminals. Facial features changed as an offender aged, and growing a mustache or beard might be enough to alter a man’s appearance and make identification difficult. Since mug shots were filed under the offender’s name, an enterprising criminal could simply adopt an alias, and many did.

Enter Alphonse Bertillon, a clerk at the headquarters of the Paris police who grew weary of filing reports containing brief and vague references to an offender’s appearance. Thanks to his father, a noted anthropologist, Bertillon was familiar with anthropometry, the scientific study of the measurements and proportions of the human body. One day in 1879, as he shuffled paper, he realized that recording a criminal’s exact anthropometric measurements should make it easy to identify repeat offenders. His superiors, however, scoffed at the idea that science could be used to fight crime. Three years passed before Bertillon was permitted to begin taking measurements of suspects to test his theory. Within a year he had identified enough recidivists to prove the system worked. France’s national prison system adopted bertillonage in 1885 ; police forces and penal institutions in other European countries soon signed on.

Robert McClaughry, Joliet’s forward-thinking warden, brought bertillonage to the United States. Recording body measurements became part of Joliet’s intake routine for new inmates in 1887, and McClaughry encouraged other prisons to adopt the system to catch repeat offenders. “It substitutes certainty for uncertainty,” he asserted, “a thoroughly reliable identification for the shrewd guess of the detective, or the scarcely more reliable testimony of the photograph.” Police forces and prison officials across the country embraced the new crime-fighting technology. Within a decade, 150 American police forces and prisons were using the system. Possessing a set of Bertillon’s tools, one American criminologist would note, “became the distinguishing mark of the modern police organization.”

But bertillonage had its drawbacks—and its detractors. Carefully measuring feet, ears, and fingers of offenders like Thomas Neill Cream was a time-consuming process and skilled, trained technicians were needed to ensure the results were accurate. Tools became worn or bent through constant use, producing results that could match an innocent man to the crimes of someone of similar size and build. Since the premise underlying the entire system was that bone size remained constant, bertillonage could not be used to keep track of offenders who had not reached maturity. And there was no central registry, making it difficult to trace a suspect who refused to reveal where he had lived or worked before his arrest. Some prison officials also questioned the fairness of keeping detailed records of men who had served their time and might never break the law again. McClaughry’s counterargument, that the records were checked only when a former inmate reoffended, highlighted the system’s most serious flaw—finding matching measurements simply proved that a suspect in custody had a criminal record. Unlike fingerprints, which were still years away from being accepted as a forensic tool, Bertillon records could not link an unknown offender to the scene of a crime. “No man can be pursued by the police or by any detective,” McClaughry admitted at a national meeting of wardens in 1890, “by means of this system.”

When Cream emerged from behind the walls of Joliet in the summer of 1891, there was little to connect him with his dark, murderous past. He was a doctor from Canada who had earned a license to practice from one of the world’s most respected medical colleges. He was also a new kind of killer, choosing victims at random and killing without remorse. A cold-blooded fiend who murdered, the Chicago Daily Tribune would later declare in disbelief, “simply for the sake of murder.” A serial killer, and one of the most brutal and prolific in history. Herman Webster Mudgett, a doctor who went by the name H. H. Holmes, killed at least nine people and would come to be considered one of America’s first serial killers. But by the time Holmes claimed his first victim in 1891, and long before the infamous Jack the Ripper terrorized London in 1888, Cream was suspected of killing as many as six people, most of them deliberately poisoned with tainted medicine. His latest victim had been the husband of his mistress, and this was the murder that had consigned him to a hovel-like cell in Joliet. His earlier victims—two in Canada, including his wife, and three more in Chicago—were young women who were pregnant and desperate to induce an abortion; they had made the tragic mistake of trusting their doctor with their lives.

In an era when police investigations were often cursory and forensic science was in its infancy, detectives lacked the tools and expertise needed to track down such a formidable foe. Few could imagine such monsters existed. But this only partly explains how Cream had gotten away with murder in two countries before he finally had been locked up in Joliet. Cream’s credentials and professional status, bungled investigations, corrupt police and justice officials, failed prosecutions, and missed opportunities allowed him to kill, again and again.

The thin paper trail documenting Cream’s shocking crimes was scattered from small-town Canada to Illinois, with only fading memories, forgotten court files, and yellowing newspaper clippings to connect the dots. The Bertillon identification system, cutting-edge technology for its time, was powerless to prevent a convicted criminal from vanishing like a ghost. If a former inmate wanted to disappear after his release, to hide his past—as Cream most certainly did—all he had to do was change his name.